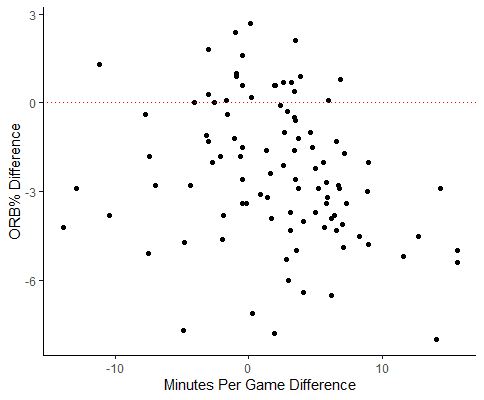

To find out, I looked at the top 50 players in terms of ORB% from the past 4 seasons on Sports Reference. I removed players whose top 50 ORB% season was his last in college and any players who transferred. I then calculated the minutes per game increase or decrease following the elite ORB% season and how much the player's ORB% changed after the top 50 season. For instance, Michigan State's Nick Ward had a top 50 ORB% season in 2017-2018, so I compared his minutes per game and ORB% to the following 2018-2019 season. Here's the results:

As you can see, the vast majority of players experienced the expected decline in ORB% as their minutes increased. To answer the first question posed in the introduction, most players saw a decline of about 1-6%. While it's a decent decrease, to be in the top 50 in terms of ORB%, these players had an ORB% of somewhere between 13-18% in their standout season. Even a drop of 6% in the next season would mean at worst an ORB% of 7%. This is hardly elite anymore, but isn't completely awful.

Somewhat surprisingly, ORB% also decreased in players who experienced significant minute reductions. You'd think that a player's ORB% would go up with fewer minutes because they'd have to be locked in on getting offensive rebounds for less time per game to maintain the same ORB%. Perhaps ORB% mostly declines along with minutes due to underlying poor play. For instance, coaches may have been unimpressed during the offseason/beginning few games and decided to cut these players' minutes. In this scenario, the players may have simply been not as good as they were in the prior season which could yield fewer offensive boards and a lower ORB%.

While ORB% seems to decline after an elite season for most players, there are a few who buck this trend and preserve or improve their already high ORB% in the following season. Most of such players experienced minimal changes in the amount of minutes that they played. This might suggest that these players were already operating in a role that maximized their offensive rebounding efficiency. By either pure luck or intentional strategy, their coaches opted to keep these players' minutes the same and benefited from another excellent ORB% season. Unfortunately, there are also plenty of players who undermined this pattern as they played roughly the same minutes the following season and saw their ORB% drop, sometimes significantly. Thus, getting a player to maintain an exceptional ORB% isn't as simple as holding his minutes the same.

Given that we largely see a decline in ORB% in most players who saw more minutes in the next season, it's important to take a look at what's driving this drop. Is it that players are getting fewer offensive rebounds overall in the following season, or is the minute increase greater than a player's offensive rebounding increase? To achieve this, we can color each point of the above graph according to how many more (or fewer) offensive rebounds per game a player got in the next season. Green indicates a large increase and red indicates a large decrease. Here's what the new, color-coded graph looks like:

As would be expected, pretty much every player who experienced a minutes reduction also grabbed fewer offensive rebounds in the following season. It certainly makes sense as less time on the court means less opportunities to get rebounds. Also, the few standouts who were able to meet or exceed their previously impressive ORB% were actually able to get more offensive rebounds per game as well. These players were especially useful as they maintained their offensive rebounding efficiency while also increasing their volume of offensive rebounds. Most interestingly, we see from the graph that the majority of players who saw increased minutes also increased their rebounds per game. This means that their decrease in ORB% was caused by their minute increase outpacing their offensive rebounding increase. This is important because it suggests that the decrease in ORB% may not be such a bad thing after all. When these players were given expanded minutes, their offensive rebounding didn't suddenly get much worse, it just didn't improve at quite as rapid of a rate.

It's also important to consider what else these players are doing in their increased minutes. After all, most coaches won't give a guy 5-10 extra minutes per game expecting him to only focus on increasing his offensive rebounding. An area that I thought would be especially important to look at is scoring. If a player is going to play significantly more per game, they'll likely need to chip in with more points. The following graph is the same as the previous two, but is colored by the points per game increase or decrease in the following season. Like the last graph, green indicates the largest scoring increase and red represents the largest drop.

Mirroring the trend in the previous graph of players who had a minutes reduction getting fewer offensive rebounds per game, these players also scored less. Even players who kept roughly the same minutes and maintained or improved their ORB% varied in terms of if they were able to increase their scoring or not. While these players kept a high rebounding efficiency and increased their rebounding volume, scoring didn't always follow suit. Meanwhile, most players who experienced an increase in minutes also experienced a scoring boost, even if it was just a slight one. Thus, this benefit to the team serves to somewhat counteract the ORB% decline.

After diving into these three graphs, it's time to return to the second question posed in the introduction regarding if the minutes increase is worth it. The answer to this is that it really depends. The second and third graphs revealed that a decrease in ORB% isn't inherently a bad thing because players can still increase their offensive rebounding volume at the expense of some efficiency while also improving other skills such as scoring. However, the tricky part is determining whether the incremental offensive rebounding and/or scoring increase is worth sacrificing an excellent ORB%. I think it's safe to say that players such as those represented by the two green points furthest to the right on the above graph are cases where it's worth it. An increase of 5-10 points per game is likely more valuable to their respective teams than about 5% of lost ORB% considering that their rebounds per game also increased. It gets more difficult when comparing say a 1 point per game scoring increase to a 3% drop in ORB%.

Ignoring team-specific roster situations, it seems as though in general coaches may as well risk worse offensive rebounding efficiency with increased minutes in the hopes of more overall production from their players. Chasing the same elite ORB% efficiency as the previous season by keeping minutes the same appears to be just as risky. Overall, my optimism in the previous article was a little excessive because we've seen that an elite ORB% is only sustainable in rare instances. However, this sustainability doesn't seem to be desirable to aim for in the first place.

Thanks so much for reading if you've made it this far! Be sure to check out some of my other articles if you enjoyed this!